Learning Objectives

Avogadro’s Law is one of the gas laws. At the beginning of the 19th century, an Italian scientist Lorenzo Romano Amedeo Carlo Avogadro studied the relationship between the volume and the amount of substance of gas present. The results of certain experiments with gases led him to formulate a well-known Avogadro’s Law. Nov 07, 2019 Avogadro's Law is the relation which states that at the same temperature and pressure, equal volumes of all gases contain the same number of molecules.The law was described by Italian chemist and physicist Amedeo Avogadro in 1811. Avogadro’s law, also known as Avogadro’s principle or Avogadro’s hypothesis, is a gas law which states that the total number of atoms/molecules of a gas (i.e. The amount of gaseous substance) is directly proportional to the volume occupied by the gas at constant temperature and pressure. Avogadro's law is also called Avogadro's principle or Avogadro's hypothesis. Like the other ideal gas laws, Avogadro's law only approximates the behavior of real gases. Under conditions of high temperature or pressure, the law is inaccurate. The relation works best for gases held at low pressure and ordinary temperatures. Avogadro’s law also means the ideal gas constant is the same value for all gases, so: constant = p 1 V 1 /T 1 n 1 = P 2 V 2 /T 2 n 2. V 1 /n 1 = V 2 /n 2. V 1 n 2 = V 2 n 1. Where p is the pressure of a gas, V is volume, T is temperature, and n is number of moles. Examples of Avogadro’s law in Real Life Applications.

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- State the ideal gas law in terms of molecules and in terms of moles.

- Use the ideal gas law to calculate pressure change, temperature change, volume change, or the number of molecules or moles in a given volume.

- Use Avogadro’s number to convert between number of molecules and number of moles.

Figure 1. The air inside this hot air balloon flying over Putrajaya, Malaysia, is hotter than the ambient air. As a result, the balloon experiences a buoyant force pushing it upward. (credit: Kevin Poh, Flickr)

In this section, we continue to explore the thermal behavior of gases. In particular, we examine the characteristics of atoms and molecules that compose gases. (Most gases, for example nitrogen, N2, and oxygen, O2, are composed of two or more atoms. We will primarily use the term “molecule” in discussing a gas because the term can also be applied to monatomic gases, such as helium.)

Gases are easily compressed. We can see evidence of this in Table 1 in Thermal Expansion of Solids and Liquids, where you will note that gases have the largest coefficients of volume expansion. The large coefficients mean that gases expand and contract very rapidly with temperature changes. In addition, you will note that most gases expand at the same rate, or have the same β. This raises the question as to why gases should all act in nearly the same way, when liquids and solids have widely varying expansion rates.

The answer lies in the large separation of atoms and molecules in gases, compared to their sizes, as illustrated in Figure 2. Because atoms and molecules have large separations, forces between them can be ignored, except when they collide with each other during collisions. The motion of atoms and molecules (at temperatures well above the boiling temperature) is fast, such that the gas occupies all of the accessible volume and the expansion of gases is rapid. In contrast, in liquids and solids, atoms and molecules are closer together and are quite sensitive to the forces between them.

Figure 2. Atoms and molecules in a gas are typically widely separated, as shown. Because the forces between them are quite weak at these distances, the properties of a gas depend more on the number of atoms per unit volume and on temperature than on the type of atom.

To get some idea of how pressure, temperature, and volume of a gas are related to one another, consider what happens when you pump air into an initially deflated tire. The tire’s volume first increases in direct proportion to the amount of air injected, without much increase in the tire pressure. Once the tire has expanded to nearly its full size, the walls limit volume expansion. If we continue to pump air into it, the pressure increases. The pressure will further increase when the car is driven and the tires move. Most manufacturers specify optimal tire pressure for cold tires. (See Figure 3.)

Figure 3. (a) When air is pumped into a deflated tire, its volume first increases without much increase in pressure. (b) When the tire is filled to a certain point, the tire walls resist further expansion and the pressure increases with more air. (c) Once the tire is inflated, its pressure increases with temperature.

At room temperatures, collisions between atoms and molecules can be ignored. In this case, the gas is called an ideal gas, in which case the relationship between the pressure, volume, and temperature is given by the equation of state called the ideal gas law.

Ideal Gas Law

The ideal gas law states that PV = NkT, where P is the absolute pressure of a gas, V is the volume it occupies, N is the number of atoms and molecules in the gas, and T is its absolute temperature. The constant k is called the Boltzmann constant in honor of Austrian physicist Ludwig Boltzmann (1844–1906) and has the value k = 1.38 × 10−23 J/K.

The ideal gas law can be derived from basic principles, but was originally deduced from experimental measurements of Charles’ law (that volume occupied by a gas is proportional to temperature at a fixed pressure) and from Boyle’s law (that for a fixed temperature, the product PV is a constant). In the ideal gas model, the volume occupied by its atoms and molecules is a negligible fraction of V. The ideal gas law describes the behavior of real gases under most conditions. (Note, for example, that N is the total number of atoms and molecules, independent of the type of gas.)

Let us see how the ideal gas law is consistent with the behavior of filling the tire when it is pumped slowly and the temperature is constant. At first, the pressure P is essentially equal to atmospheric pressure, and the volume V increases in direct proportion to the number of atoms and molecules N put into the tire. Once the volume of the tire is constant, the equation PV = NkT predicts that the pressure should increase in proportion to the number N of atoms and molecules.

Example 1. Calculating Pressure Changes Due to Temperature Changes: Tire Pressure

Suppose your bicycle tire is fully inflated, with an absolute pressure of 7.00 × 105 Pa (a gauge pressure of just under 90.0 lb/in2) at a temperature of 18.0ºC. What is the pressure after its temperature has risen to 35.0ºC? Assume that there are no appreciable leaks or changes in volume.

Strategy

The pressure in the tire is changing only because of changes in temperature. First we need to identify what we know and what we want to know, and then identify an equation to solve for the unknown.

We know the initial pressure P0 = 7.00 × 105 Pa, the initial temperature T0 = 18.0ºC, and the final temperature Tf = 35.0ºC. We must find the final pressure Pf. How can we use the equation PV = NkT? At first, it may seem that not enough information is given, because the volume V and number of atoms N are not specified. What we can do is use the equation twice: P0V0 = NkT0 and PfVf = NkTf. If we divide PfVf by P0V0 we can come up with an equation that allows us to solve for Pf.

[latex]displaystylefrac{P_{text{f}}V_{text{f}}}{P_0V_0}=frac{N_{text{f}}kT_{text{f}}}{N_0kT_0}[/latex]

Since the volume is constant, Vf and V0 are the same and they cancel out. The same is true for Nf and N0, and k, which is a constant. Therefore,

[latex]displaystylefrac{P_{text{f}}}{P_0}=frac{T_{text{f}}}{T_0}[/latex]

We can then rearrange this to solve for Pf: [latex]P_{text{f}}=P_0frac{T_{text{f}}}{T_0}[/latex], where the temperature must be in units of kelvins, because T0 and Tf are absolute temperatures.

Solution

Convert temperatures from Celsius to Kelvin:

T0 = (18.0 + 273)K = 291 K

Tf = (35.0 + 273)K = 308 K

Substitute the known values into the equation.

[latex]displaystyle{P}_{text{f}}=P_0frac{T_{text{f}}}{T_0}=7.00times10^5text{ Pa}left(frac{308text{ K}}{291text{ K}}right)=7.41times10^5text{ Pa}[/latex]

Discussion

The final temperature is about 6% greater than the original temperature, so the final pressure is about 6% greater as well. Note that absolute pressure and absolute temperature must be used in the ideal gas law.

Making Connections: Take-Home Experiment—Refrigerating a Balloon

Inflate a balloon at room temperature. Leave the inflated balloon in the refrigerator overnight. What happens to the balloon, and why?

Example 2. Calculating the Number of Molecules in a Cubic Meter of Gas

How many molecules are in a typical object, such as gas in a tire or water in a drink? We can use the ideal gas law to give us an idea of how large N typically is.

Calculate the number of molecules in a cubic meter of gas at standard temperature and pressure (STP), which is defined to be 0ºC and atmospheric pressure.

Strategy

Because pressure, volume, and temperature are all specified, we can use the ideal gas law PV = NkT, to find N.

Solution

Identify the knowns:

[latex]begin{array}{lll}T&=&0^{circ}text{C}=273text{ K}P&=&1.01times10^5text{ Pa}V&=&1.00text{ m}^3k&=&1.38times10^{-23}text{ J/K}end{array}[/latex]

Identify the unknown: number of molecules, N.

Rearrange the ideal gas law to solve for N:

[latex]begin{array}{lll}PV&=&NkTN&=&frac{PV}{kT}end{array}[/latex]

Substitute the known values into the equation and solve for N:

[latex]displaystyle{N}=frac{PV}{kT}=frac{left(1.01times10^5text{ Pa}right)left(1.00text{ m}^3right)}{left(1.38times10^{-23}text{ J/K}right)left(273text{ K}right)}=2.68times10^{25}text{ molecules}[/latex]

Discussion

This number is undeniably large, considering that a gas is mostly empty space. N is huge, even in small volumes. For example, 1 cm3 of a gas at STP has 2.68 × 1019 molecules in it. Once again, note that N is the same for all types or mixtures of gases.

Moles and Avogadro’s Number

It is sometimes convenient to work with a unit other than molecules when measuring the amount of substance. A mole (abbreviated mol) is defined to be the amount of a substance that contains as many atoms or molecules as there are atoms in exactly 12 grams (0.012 kg) of carbon-12. The actual number of atoms or molecules in one mole is called Avogadro’s number (NA), in recognition of Italian scientist Amedeo Avogadro (1776–1856). He developed the concept of the mole, based on the hypothesis that equal volumes of gas, at the same pressure and temperature, contain equal numbers of molecules. That is, the number is independent of the type of gas. This hypothesis has been confirmed, and the value of Avogadro’s number is NA = 6.02 × 1023 mol−1.

Avogadro’s Number

One mole always contains 6.02 × 1023 particles (atoms or molecules), independent of the element or substance. A mole of any substance has a mass in grams equal to its molecular mass, which can be calculated from the atomic masses given in the periodic table of elements.

NA = 6.02 × 1023 mol−1

Figure 4. How big is a mole? On a macroscopic level, one mole of table tennis balls would cover the Earth to a depth of about 40 km.

Check Your Understanding

The active ingredient in a Tylenol pill is 325 mg of acetaminophen (C8H9NO2). Find the number of active molecules of acetaminophen in a single pill.

Solution

We first need to calculate the molar mass (the mass of one mole) of acetaminophen. To do this, we need to multiply the number of atoms of each element by the element’s atomic mass.

(8 moles of carbon)(12 grams/mole) + (9 moles hydrogen)(1 gram/mole) + (1 mole nitrogen)(14 grams/mole) + (2 moles oxygen)(16 grams/mole) = 151 g

Then we need to calculate the number of moles in 325 mg.

[latex]displaystyleleft(frac{325text{ mg}}{151text{ grams/mole}}right)left(frac{1text{ gram}}{1000text{ mg}}right)=2.15times10^{-3}text{ moles}[/latex]

Then use Avogadro’s number to calculate the number of molecules.

N = (2.15 × 10−3 moles)(6.02 × 1023 molecules/mole) = 1.30 × 1021 molecules

Example 3. Calculating Moles per Cubic Meter and Liters per Mole

Calculate the following:

- The number of moles in 1.00 m3 of gas at STP

- The number of liters of gas per mole.

Strategy and Solution

- We are asked to find the number of moles per cubic meter, and we know from Example 2 that the number of molecules per cubic meter at STP is 2.68 × 1025. The number of moles can be found by dividing the number of molecules by Avogadro’s number. We let n stand for the number of moles,

[latex]{m}text{ mol/m}^3=frac{Ntext{ molecules/m}^3}{6.02times10^{23}text{ molecules/mol}}=frac{2.68times10^{25}text{ molecules/m}^3}{6.02times10^{23}text{ molecules/mol}}=44.5text{ mol/m}^3[/latex] - Using the value obtained for the number of moles in a cubic meter, and converting cubic meters to liters, we obtain [latex]frac{left(10^3text{ L/m}^3right)}{44.5text{ mol/m}^3}=22.5text{ L/mol}[/latex]

Discussion

This value is very close to the accepted value of 22.4 L/mol. The slight difference is due to rounding errors caused by using three-digit input. Again this number is the same for all gases. In other words, it is independent of the gas.

The (average) molar weight of air (approximately 80% N2 and 20% O2 is M = 28.8 g. Thus the mass of one cubic meter of air is 1.28 kg. If a living room has dimensions 5 m × 5 m × 3 m, the mass of air inside the room is 96 kg, which is the typical mass of a human.

Check Your Understanding

The density of air at standard conditions (P = 1 atm and T = 20ºC) is 1.28 kg/m3. At what pressure is the density 0.64 kg/m3 if the temperature and number of molecules are kept constant?

Solution

The best way to approach this question is to think about what is happening. If the density drops to half its original value and no molecules are lost, then the volume must double. If we look at the equation PV = NkT, we see that when the temperature is constant, the pressure is inversely proportional to volume. Therefore, if the volume doubles, the pressure must drop to half its original value, and Pf = 0.50 atm.

The Ideal Gas Law Restated Using Moles

A very common expression of the ideal gas law uses the number of moles, n, rather than the number of atoms and molecules, N. We start from the ideal gas law, PV = NkT, and multiply and divide the equation by Avogadro’s number NA. This gives [latex]PV=frac{N}{N_{text{A}}}N_{text{A}}kT[/latex].

Note that [latex]n=frac{N}{N_{text{A}}}[/latex] is the number of moles. We define the universal gas constant R=NAk, and obtain the ideal gas law in terms of moles.

Ideal Gas Law (in terms of moles)

The ideal gas law (in terms of moles) is PV = nRT.

The numerical value of R in SI units is R = NAk = (6.02 × 1023 mol−1)(1.38 × 10−23 J/K) = 8.31 J/mol · K.

In other units,

R = 1.99 cal/mol · K

R = 0.0821 L · atm/mol · K

You can use whichever value of R is most convenient for a particular problem.

Example 4. Calculating Number of Moles: Gas in a Bike Tire

How many moles of gas are in a bike tire with a volume of 2.00 × 10−3 m3(2.00 L), a pressure of 7.00 × 105 Pa (a gauge pressure of just under 90.0 lb/in2), and at a temperature of 18.0ºC?

Strategy

Identify the knowns and unknowns, and choose an equation to solve for the unknown. In this case, we solve the ideal gas law, PV = nRT, for the number of moles n.

Solution

Identify the knowns:

[latex]begin{array}{lll}P&=&7.00times10^5text{ Pa}V&=&2.00times10^{-3}text{ m}^3T&=&18.0^{circ}text{C}=291text{ K}R&=&8.31text{ J/mol}cdottext{ K}end{array}[/latex]

Rearrange the equation to solve for n and substitute known values.

[latex]begin{array}{lll}n&=&frac{PV}{RT}=frac{left(7.00times10^5text{ Pa}right)left(2.00times10^{-3}text{ m}^3right)}{left(8.31text{ J/mol}cdottext{ K}right)left(291text{ K}right)}text{ }&=&0.579text{ mol}end{array}[/latex]

Discussion

The most convenient choice for R in this case is 8.31 J/mol · K, because our known quantities are in SI units. The pressure and temperature are obtained from the initial conditions in Example 1, but we would get the same answer if we used the final values.

The ideal gas law can be considered to be another manifestation of the law of conservation of energy (see Conservation of Energy). Work done on a gas results in an increase in its energy, increasing pressure and/or temperature, or decreasing volume. This increased energy can also be viewed as increased internal kinetic energy, given the gas’s atoms and molecules.

The Ideal Gas Law and Energy

Let us now examine the role of energy in the behavior of gases. When you inflate a bike tire by hand, you do work by repeatedly exerting a force through a distance. This energy goes into increasing the pressure of air inside the tire and increasing the temperature of the pump and the air.

The ideal gas law is closely related to energy: the units on both sides are joules. The right-hand side of the ideal gas law in PV = NkT is NkT. This term is roughly the amount of translational kinetic energy of N atoms or molecules at an absolute temperature T, as we shall see formally in Kinetic Theory: Atomic and Molecular Explanation of Pressure and Temperature. The left-hand side of the ideal gas law is PV, which also has the units of joules. We know from our study of fluids that pressure is one type of potential energy per unit volume, so pressure multiplied by volume is energy. The important point is that there is energy in a gas related to both its pressure and its volume. The energy can be changed when the gas is doing work as it expands—something we explore in Heat and Heat Transfer Methods—similar to what occurs in gasoline or steam engines and turbines.

Problem-Solving Strategy: The Ideal Gas Law

Step 1. Examine the situation to determine that an ideal gas is involved. Most gases are nearly ideal.

Step 2. Make a list of what quantities are given, or can be inferred from the problem as stated (identify the known quantities). Convert known values into proper SI units (K for temperature, Pa for pressure, m3 for volume, molecules for N, and moles for n).

Step 3. Identify exactly what needs to be determined in the problem (identify the unknown quantities). A written list is useful.

Step 4. Determine whether the number of molecules or the number of moles is known, in order to decide which form of the ideal gas law to use. The first form is PV = NkT and involves N, the number of atoms or molecules. The second form is PV = nRT and involves n, the number of moles.

Step 5. Solve the ideal gas law for the quantity to be determined (the unknown quantity). You may need to take a ratio of final states to initial states to eliminate the unknown quantities that are kept fixed.

Step 6. Substitute the known quantities, along with their units, into the appropriate equation, and obtain numerical solutions complete with units. Be certain to use absolute temperature and absolute pressure.

Step 7. Check the answer to see if it is reasonable: Does it make sense?

Check Your Understanding

Liquids and solids have densities about 1000 times greater than gases. Explain how this implies that the distances between atoms and molecules in gases are about 10 times greater than the size of their atoms and molecules.

Solution

Atoms and molecules are close together in solids and liquids. In gases they are separated by empty space. Thus gases have lower densities than liquids and solids. Density is mass per unit volume, and volume is related to the size of a body (such as a sphere) cubed. So if the distance between atoms and molecules increases by a factor of 10, then the volume occupied increases by a factor of 1000, and the density decreases by a factor of 1000.

Section Summary

- The ideal gas law relates the pressure and volume of a gas to the number of gas molecules and the temperature of the gas.

- The ideal gas law can be written in terms of the number of molecules of gas: PV = NkT, where P is pressure, V is volume, T is temperature, N is number of molecules, and k is the Boltzmann constant k = 1.38 × 10–23 J/K.

- A mole is the number of atoms in a 12-g sample of carbon-12.

- The number of molecules in a mole is called Avogadro’s number NA, NA = 6.02 × 1023 mol−1.

- A mole of any substance has a mass in grams equal to its molecular weight, which can be determined from the periodic table of elements.

- The ideal gas law can also be written and solved in terms of the number of moles of gas: PV = nRT, where n is number of moles and R is the universal gas constant, R = 8.31 J/mol ⋅ K.

- The ideal gas law is generally valid at temperatures well above the boiling temperature.

Conceptual Questions

Find out the human population of Earth. Is there a mole of people inhabiting Earth? If the average mass of a person is 60 kg, calculate the mass of a mole of people. How does the mass of a mole of people compare with the mass of Earth?

Under what circumstances would you expect a gas to behave significantly differently than predicted by the ideal gas law?

A constant-volume gas thermometer contains a fixed amount of gas. What property of the gas is measured to indicate its temperature?

Avogadro's Gas Law Worksheet

Problems & Exercises

Avogadro's Law Formulas

- The gauge pressure in your car tires is 2.50 × 105 N/m2 at a temperature of 35.0ºC when you drive it onto a ferry boat to Alaska. What is their gauge pressure later, when their temperature has dropped to –40.0ºC?

- Convert an absolute pressure of 7.00 × 105 N/m2 to gauge pressure in lb/in2. (This value was stated to be just less than 90.0 lb/in2 in Example 4. Is it?)

- Suppose a gas-filled incandescent light bulb is manufactured so that the gas inside the bulb is at atmospheric pressure when the bulb has a temperature of 20.0ºC. (a) Find the gauge pressure inside such a bulb when it is hot, assuming its average temperature is 60.0ºC (an approximation) and neglecting any change in volume due to thermal expansion or gas leaks. (b) The actual final pressure for the light bulb will be less than calculated in part (a) because the glass bulb will expand. What will the actual final pressure be, taking this into account? Is this a negligible difference?

- Large helium-filled balloons are used to lift scientific equipment to high altitudes. (a) What is the pressure inside such a balloon if it starts out at sea level with a temperature of 10.0ºC and rises to an altitude where its volume is twenty times the original volume and its temperature is –50.0ºC? (b) What is the gauge pressure? (Assume atmospheric pressure is constant.)

- Confirm that the units of nRT are those of energy for each value of R: (a) 8.31 J/mol ⋅ K, (b) 1.99 cal/mol ⋅ K, and (c) 0.0821 L ⋅ atm/mol ⋅ K.

- In the text, it was shown that N/V = 2.68 × 1025 m−3 for gas at STP. (a) Show that this quantity is equivalent to N/V = 2.68 × 1019 cm−3, as stated. (b) About how many atoms are there in one μm3 (a cubic micrometer) at STP? (c) What does your answer to part (b) imply about the separation of atoms and molecules?

- Calculate the number of moles in the 2.00-L volume of air in the lungs of the average person. Note that the air is at 37.0ºC (body temperature).

- An airplane passenger has 100 cm3 of air in his stomach just before the plane takes off from a sea-level airport. What volume will the air have at cruising altitude if cabin pressure drops to 7.50 × 104 N/m2?

- (a) What is the volume (in km3) of Avogadro’s number of sand grains if each grain is a cube and has sides that are 1.0 mm long? (b) How many kilometers of beaches in length would this cover if the beach averages 100 m in width and 10.0 m in depth? Neglect air spaces between grains.

- An expensive vacuum system can achieve a pressure as low as 1.00 × 10–7 N/m2 at 20ºC. How many atoms are there in a cubic centimeter at this pressure and temperature?

- The number density of gas atoms at a certain location in the space above our planet is about 1.00 × 1011 m−3, and the pressure is 2.75 × 10–10 N/m2 in this space. What is the temperature there?

- A bicycle tire has a pressure of 7.00 × 105 N/m2 at a temperature of 18.0ºC and contains 2.00 L of gas. What will its pressure be if you let out an amount of air that has a volume of 100cm3 at atmospheric pressure? Assume tire temperature and volume remain constant.

- A high-pressure gas cylinder contains 50.0 L of toxic gas at a pressure of 1.40 × 107 N/m2 and a temperature of 25.0ºC. Its valve leaks after the cylinder is dropped. The cylinder is cooled to dry ice temperature (–78.5ºC) to reduce the leak rate and pressure so that it can be safely repaired. (a) What is the final pressure in the tank, assuming a negligible amount of gas leaks while being cooled and that there is no phase change? (b) What is the final pressure if one-tenth of the gas escapes? (c) To what temperature must the tank be cooled to reduce the pressure to 1.00 atm (assuming the gas does not change phase and that there is no leakage during cooling)? (d) Does cooling the tank appear to be a practical solution?

- Find the number of moles in 2.00 L of gas at 35.0ºC and under 7.41 × 107 N/m2 of pressure.

- Calculate the depth to which Avogadro’s number of table tennis balls would cover Earth. Each ball has a diameter of 3.75 cm. Assume the space between balls adds an extra 25.0% to their volume and assume they are not crushed by their own weight.

- (a) What is the gauge pressure in a 25.0ºC car tire containing 3.60 mol of gas in a 30.0 L volume? (b) What will its gauge pressure be if you add 1.00 L of gas originally at atmospheric pressure and 25.0ºC? Assume the temperature returns to 25.0ºC and the volume remains constant.

- (a) In the deep space between galaxies, the density of atoms is as low as 106 atoms/m3, and the temperature is a frigid 2.7 K. What is the pressure? (b) What volume (in m3) is occupied by 1 mol of gas? (c) If this volume is a cube, what is the length of its sides in kilometers?

Glossary

ideal gas law: the physical law that relates the pressure and volume of a gas to the number of gas molecules or number of moles of gas and the temperature of the gas

Boltzmann constant:k, a physical constant that relates energy to temperature; k = 1.38 × 10–23 J/K

Avogadro’s number:NA, the number of molecules or atoms in one mole of a substance; NA = 6.02 × 1023 particles/mole

mole: the quantity of a substance whose mass (in grams) is equal to its molecular mass

Selected Solutions to Problems & Exercises

Avogadro's Law Gases

1. 1.62 atm

3. (a) 0.136 atm; (b) 0.135 atm. The difference between this value and the value from part (a) is negligible.

5. (a) [latex]text{nRT}=left(text{mol}right)left(text{J/mol}cdot text{K}right)left(text{K}right)=text{J}[/latex];

(b) [latex]text{nRT}=left(text{mol}right)left(text{cal/mol}cdot text{K}right)left(text{K}right)=text{cal}[/latex];

(c) [latex]begin{array}{lll}text{nRT}& =& left(text{mol}right)left(text{L}cdot text{atm/mol}cdot text{K}right)left(text{K}right) & =& text{L}cdot text{atm}=left({text{m}}^{3}right)left({text{N/m}}^{2}right) & =& text{N}cdot text{m}=text{J}end{array}[/latex]

7. 7.86 × 10−2 mol

9. (a) 6.02 × 105 km3; (b) 6.02 × 108 km

11. −73.9ºC

13. (a) 9.14 × 106 N/m2; (b) 8.23 × 106 N/m2; (c) 2.16 K; (d) No. The final temperature needed is much too low to be easily achieved for a large object.

15. 41 km

17. (a) 3.7 × 10−17 Pa; (b) 6.0 × 1017 m3; (c) 8.4 × 102 km

For most solids and liquids it is convenient to obtain the amount of substance (and the number of particles, if we want it) from the mass. In the section on The Molar Mass numerous such calculations using molar mass were done. In the case of gases, however, accurate measurement of mass is not so simple. Think about how you would weigh a balloon filled with helium, for example. Because it is buoyed up by the air it displaces, such a balloon would force a balance pan up instead of down, and a negative weight would be obtained.

The mass of a gas can be obtained by weighing a truly empty container (with a perfect vacuum), and then filling and re-weighing the container. But this is a time-consuming, inconvenient, and sometimes dangerous procedure. (Such a container might implode—explode inward—due to the difference between atmospheric pressure outside and zero pressure within.)

A more convenient way of obtaining the amount of substance in a gaseous sample is suggested by the data on molar volumes in Table (PageIndex{1}). Remember that a molar quantity (a quantity divided by the amount of substance) refers to the same number of particles.

| Substance | Formula | Molar Volume/liter mol–1 |

|---|---|---|

| Hydrogen | H2(g) | 22.43 |

| Neon | Ne(g) | 22.44 |

| Oxygen | O2(g) | 22.39 |

| Nitrogen | N2(g) | 22.40 |

| Carbon dioxide | CO2(g) | 22.26 |

| Ammonia | NH2(g) | 22.09 |

The data in Table (PageIndex{1}), then, indicate that for a variety of gases, 6.022 × 1023 molecules occupy almost exactly the same volume (the molar volume) if the temperature and pressure are held constant. We define Standard Temperature and Pressure (STP) for gases as 0°C and 1.00 atm (101.3 kPa) to establish convenient conditions for comparing the molar volumes of gases.

The molar volume is close to 22.4 liters (22.4 dm3) for virtually all gases. That equal volumes of gases at the same temperature and pressure contain equal numbers of molecules was first suggested in 1811 by the Italian chemist Amadeo Avogadro (1776 to 1856). Consequently it is called Avogadro’s law or Avogadro’s hypothesis.

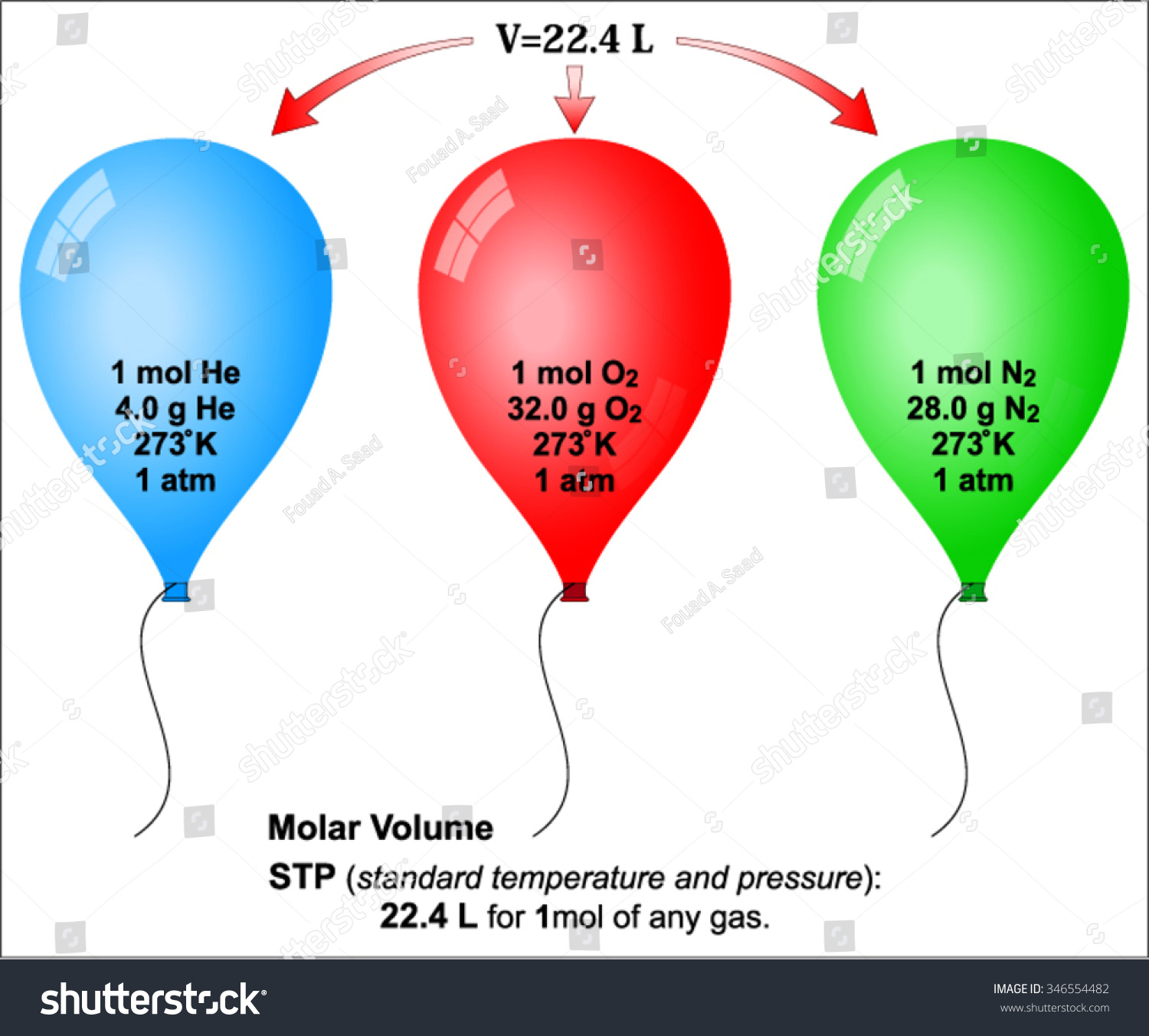

Avogadro’s law has two important messages. First, it says that molar volumes of all gases are the same at a given temperature and pressure. Therefore, even if we do not know what gas we are dealing with, we can still find the amount of substance. The image below demonstrates this concept. All 3 balloons are full of different gases, yet have the same number of moles and therefore the same volume (22.4 Liters).

Second, we expect that if a particular volume corresponds to a certain number of molecules, twice that volume would contain twice as many molecules. In other words, doubling the volume corresponds to doubling the amount of substance, halving the volume corresponds to halving the amount, and so on.

In general, if we multiply the volume by some factor, say x, then we also multiply the amount of substance by that same factor x. Such a relationship is called direct proportionality and may be expressed mathematically as

[text{V (propto) n}label{1}]

where the symbol (propto) means “is proportional to.”

For a simple demonstration of this concept, play with Concord Consortium's tool shown below, which allows you to manipulate the number of gas molecules in an a certain area and observe the effects on the volume. Try beginning with the default 120 molecules and observing the volume. Then cut the number of molecules in half to 60 and see what affect that has on the volume...To begin the animation, press the play at the bottom of the screen.

Any proportion, such as Equation (ref{1}) can be changed to an equivalent equation if one side is multiplied by a proportionality constant, such a kA in Equation(ref{2}):

[text{V} = text{k}_Atext{n}label{2}]

If we know kA for a gas, we can determine the amount of substance from Equation (ref{2}).

The situation is complicated by the fact that the volume of a gas depends on pressure and temperature, as well as on the amount of substance. That is, kA will vary as temperature and pressure change. Therefore we need quantitative information about the effects of pressure and temperature on the volume of a gas before we can explore the relationship between amount of substance and volume.

Contributors

Avogadro's Law Experiments

Ed Vitz (Kutztown University), John W. Moore (UW-Madison), Justin Shorb (Hope College), Xavier Prat-Resina (University of Minnesota Rochester), Tim Wendorff, and Adam Hahn.

Comments are closed.